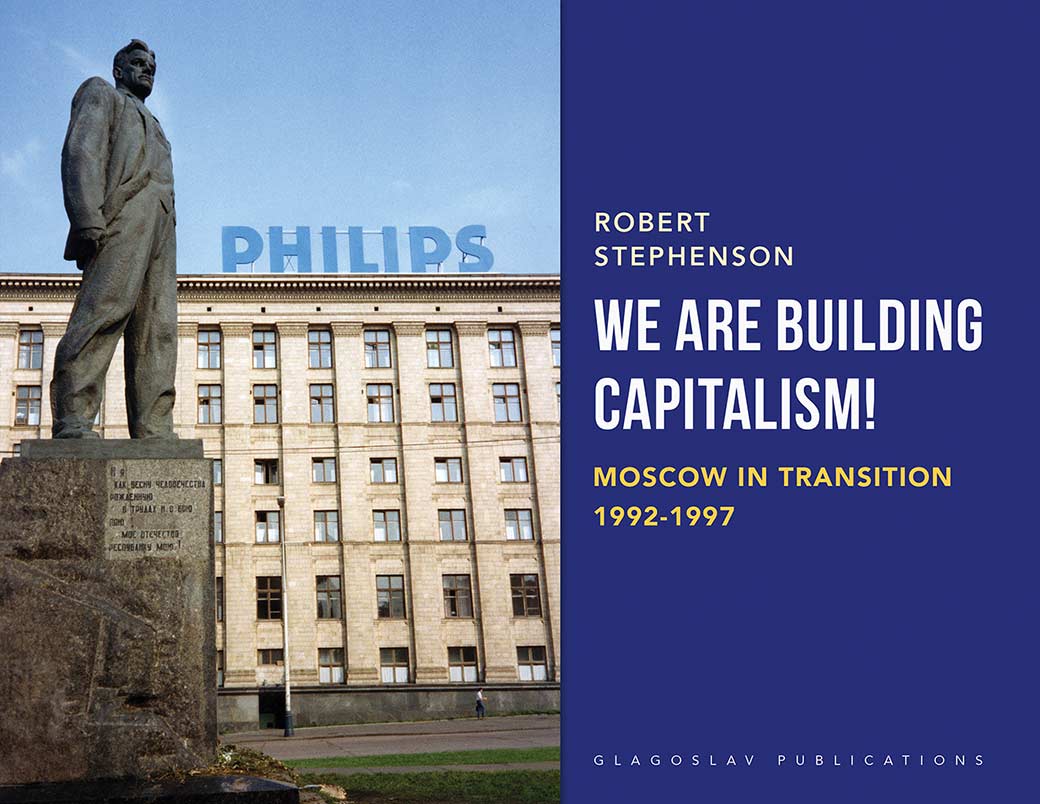

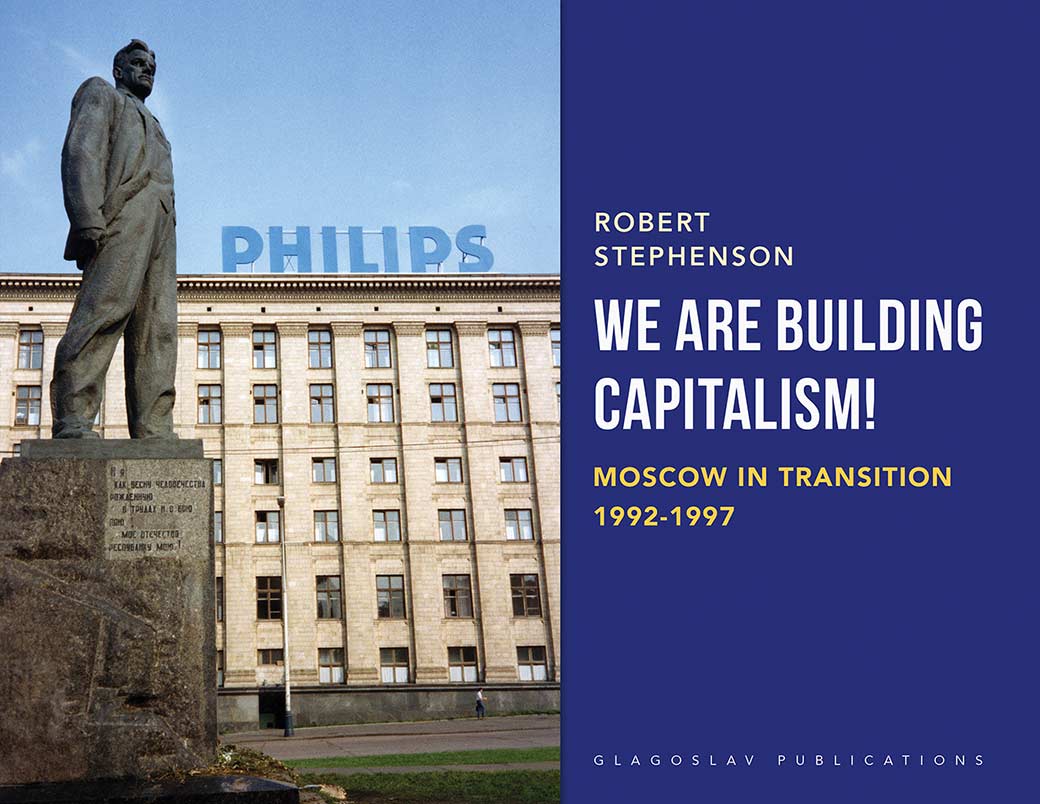

‘We Are Building Capitalism! Moscow in Transition, 1992-1997’, by Robert Stephenson (Glagoslav, 2019, ISBN 978-1-912894-02-4)

In this age of smartphones, Instagram, dashcams and drones, we count on a rich supply of images of the world around us, whether we are tourists checking out a hotel’s environs on Google Streetview before booking, or Bellingcat searching Russian soldiers’ Vkontakte pages for pictures to geolocate deployments in the Donbas. We can easily forget how new this visual abundance really is, and take for granted our capacity to mine visual evidence as easily as written text.

It is, after all, a tremendously valuable additional source, as is demonstrated by this collection of photographs from Moscow in the midst of the likhie 1990s – ‘dashing’, ‘wild’ or roaring,’ depending on choice or prejudice. This was a Moscow by turns tawdry and elegant, miserable and modernising, drab and violent – as Vladimir Gel’man says in his introduction, it is not just a companion to a social history of the time, it is a book that “has its own protagonist: Moscow.” (p11) As someone who also has his fascination with this vibrant and , well, likhyi city, I can understand what led Robert Stephenson, a British civil servant sent there as a “technical specialist” in the days when such an attachment was still possible, to chronicle the city’s spaces and structures, (numerous) traumas and (fewer) triumphs.

This is largely a collection of photographs. There are accompanying captions and some sections explaining the context for those who may not know about the 1993 shelling of parliament or the reconstruction of the Cathedral of Christ Saviour, but to be honest I suspect most who pick up with book will know the backdrop. They may also know today’s Moscow, with its shining trams, hipster food malls and wifi. In many ways it is precisely the continuities and contrasts with the 1990s that will be so striking to them, a reminder that not too long ago, Novy Arbat was still Kalinin Street, the Red October factory still made chocolate and the banana was still a novelty.

Stephenson was a chronicler, not a high-concept artist. This is not an Instagram-friendly collection of arty confections, but rather a wide-eyed visual diary of the times. Some of the pictures are unremarkable, some a little cliched – no doubt exactly what someone would likely say looking at my photo stream – but they are honest, not staged, and precisely offer up a record of the minutiae of life in that transition era: a toppled and defaced statue of Khrushchev, the bleak and crumbling façade of the pre-remont Narkomfin building, a crowd whose clothes look more Soviet than modern, a skyline where the Rossiya hotel still looms in its ugly bulkiness but no cyberpunk Moscow-City towers reach for the clouds…

As someone who still remember the 1990s with a complex mix of nostalgia, horror and depression, this was a poignant reminder. As a scholar, though, I think this is a tremendously useful visual source, illustrating and illuminating everything from the reconstruction of the city to the reshaping of its people, economy and culture, and greatly to be welcomed.

You must be logged in to post a comment.